The Year Ahead: Still Optimistic and Still Cautious - Alex III

On the heels of a wonderful 2017 global stock market rally, several clients have expressed concern for what 2018 might bring. Ultimately, we believe the global economic expansion has further room to run, but still think we are in the latter stages of this economic expansion and bull stock market.

We would be surprised if U.S. stocks perform close to 2017 returns given that we believe much of the good news is currently baked into stock prices. Consensus forecasts are for just 5% returns for large U.S. stocks. We have more optimism for international stocks in 2018 because those stocks don’t seem as expensive and seem better poised for continued earnings growth. Given the lack of any meaningful stock correction (a 5-20% downturn) since February 2016, we expect stocks moves in 2018 to be bumpier unless the good news continues rolling in unabated.

We have muted expectations in 2018 regarding bonds. Rising interest rates provide a natural headwind for bond returns; therefore, we are expecting zero to low single-digit returns. The role of bonds in our portfolios, given their low yields and rising interest rates in the U.S., is primarily to help mitigate a stock bear market. We hate our bonds in a bull market but love them in a bear.

The following are our reasons to be cautious for 2018:

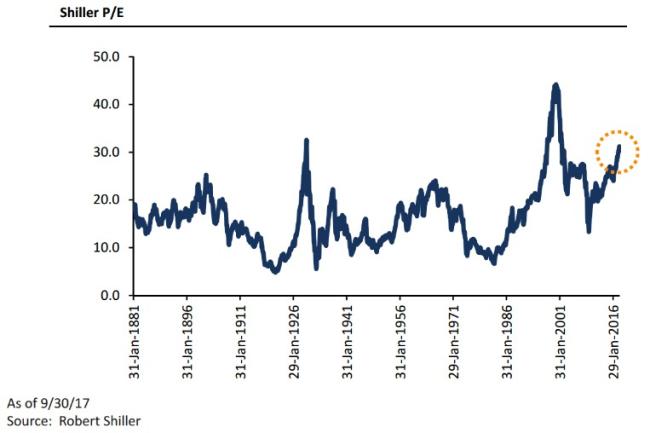

First, U.S. stocks and some other countries’ stock markets look expensive, meaning that based on certain various metrics (including the Shiller Price/Earnings Ratio shown to the right) these stocks’ prices seem high in an historical context. Most commentary we read, even the bullish ones, agree that stocks, particularly in the U.S., might have risen too high, too fast, compared to their corporate earnings. However, high prices or valuations are not usually the only factor for a bubble.

To quote Jeremy Grantham of GMO, who has done extensive research on investment bubbles (underlines are mine):

So let’s start by looking very hard at all the great bubbles of the past, searching for useful guides to the future. The classic examples are not just characterized by higher-than-average prices. Price alone seems to me now to be by no means a sufficient sign of an impending bubble break. Among other factors, indicators of extremes of euphoria seem much more important than price. Ben Graham, as quoted two quarterly letters ago, said that as far as he could see no bubble had ever broken (by 1963) without being accompanied by signs of real excess such as those found in 1929.Two months ago, Robert Shiller also made the point (in the Sunday New York Times) – as I will do – that not nearly enough signs of euphoria were yet present to make this look like a late-stage bubble. (Although in my opinion they have finally begun to pick up in the last two or three months.) And Robert Shiller was one of a very small group predicting a future market collapse in 1999, and one of a few handfuls with us in 2006 focusing on the future risks from an unprecedented US housing bubble breaking due to vulnerable mortgages. (Bracing Yourself for a Possible Near-Term Melt-Up, 1/3/2018)

Now, a bear market can certainly occur without a bubble. A bear market is defined as a loss of more than 20%, and most bear markets are a result of a recession. Bubbles usually ‘pop’ with losses much more than 20%. For example, the S&P 500 lost almost 57% from the high in October 2007 to the low in April 2009.

Second, the lack of meaningful stock market corrections in the U.S. since February 2016 is a bit concerning. Since then we have barely had a correction of 5%. Plus, the S&P 500 Index experienced no calendar month of negative returns in 2017 and only one in the past 21 months. The global economic and earnings surprises in 2017 were good news, but we have not had even a minor correction in almost two years. This does not mean the next downturn will lead us right into in a bear market, but we do think some bad news (or just not as good as 2016/2017) could push stocks down 10-20%.

Third, inflation rising much faster than anticipated might cause the Federal Reserve to increase interest rates more than the two or three times currently anticipated for 2018. This might cause investors to worry that much higher interest rates will push the U.S. into a recession more quickly. Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) was 2.1% at year-end. The Federal Reserve’s target is 2%. So, right now inflation and much higher rates are not a threat if the current trend continues. However, if significant wage pressures or high oil prices negatively surprise the markets, then this could add to the reasons to be bearish. Note: The rest of the world, like the U.S., still has relatively low, persistent inflation.

Fourth, geopolitical risks have seemingly increased. How the U.S. handles the NAFTA and other trade deals, including those with China, are of important consequence to our financial markets. China’s reliance on substantial corporate debt to spur investment and economic growth for the past nine years is concerning. The standoff between the U.S. and North Korea has no good outcomes but, hopefully, both sides choose to avoid a war that, even if not nuclear, would likely cause significant damage to South Korea, one of our democratic and industrial allies. If rising tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran escalate to outright confrontation, this could further destabilize the Middle East and potentially push oil prices higher.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the reasons for optimism:

First, we do not see a U.S. recession around the corner in the next 6-12 months. Recessions are always hard to forecast, but with low inflation, low unemployment, good consumer balance sheets and good consumer sentiment, we believe there is currently a low probability of a U.S. recession. The current U.S. forecasts for growth and inflation are around 2.5% and 2.3% respectively. With this said, the U.S. may be entering the late stages of its economic expansion. Recent U.S. tax reform (or more accurately, corporate tax cuts) should have a minor positive impact on U.S. growth in the near-term, but the current consensus among economists is that it will have little positive long-term impact.

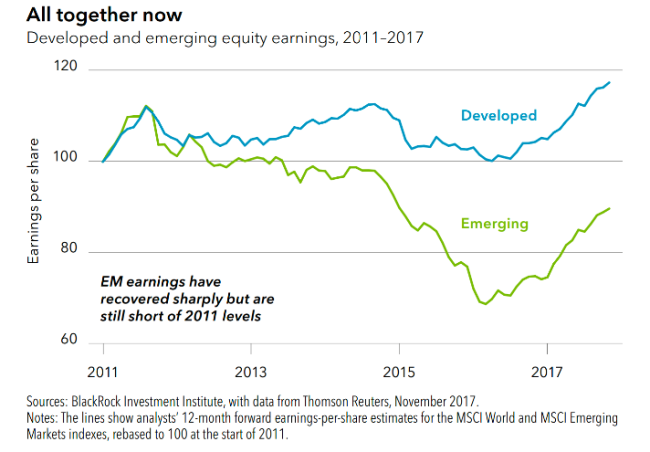

Second, the global economy is in a synchronized uptick that has not been seen in several years. The U.S., Europe, Japan and many emerging market countries are growing a bit faster than in the past and, at the same time. The breadth of the global recovery has also expanded – manufacturing figures are up in about 80% of countries, a share that has steadily increased over the past year.

Third, even though U.S. interest rates are anticipated to rise further in 2018, they will still be below the Fed’s target of less than 3%. The Federal Reserve has embarked on reversing its Quantitative Easing program, which helped keep long-term interest rates low for years, but the rate of reversal is very gradual at this point. On the other hand, the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank still maintain “loose” monetary policy, thereby continuing to stimulate their economies.

Fourth, corporate earnings around the globe continue to support increasing stock prices, or at least a bullish tone. In 2017 Thomson Reuters data show all major regions increased earnings at a clip faster than 10%, the strongest growth since the post-crisis bounce. We expect more good things in 2018, but 2017 will be a tough act to follow. Year-over-year increases will be harder to replicate. Still, we see the economic and earnings backdrop as positive for stocks, with higher valuations a potential drag, especially in the U.S. The S&P 500 is projected to post an earnings per share (EPS) gain of 10.8% for all of 2017. For 2018, the EPS of companies in the S&P 500 Index is projected to climb 13.6%. S&P 500 company revenues are expected to rise 6.8% for all of 2017 and 5.8% in 2018.

In conclusion, we are cautiously optimistic for 2018 and beyond. In many client meetings, especially for those clients approaching or in retirement, we are starting to discuss the idea of taking less stock risk. No one has a crystal ball, but it’s important to have these discussions to weigh the pros and cons of any potential changes in risk.